February 2026 Species of the Month: Ischnura posita

The Fragile Forktail (Ischnura posita) is a narrow-winged damselfly in the genus Ischnura and the family Coenagrionidae. They are among the smallest damselflies, averaging about an inch long (2.54 cm). Their range extends south to Florida, northeast to New England, west to western Oklahoma and Texas, south through Mexico, and into Guatemala. Enjoy dragonfly data collector Steve Baginski’s encounter with this species in this month’s blog post.

Not So Fragile Forktails

In 2023, my wife Gail Chastain and I began collecting odonate data at a pond on a newly-purchased 18 acre property, added to the 1,700 acre The Morton Arboretum in Lisle, IL. The site includes Fischer Pond, surrounded by trees with diverse grasses and a 100-acre tallgrass prairie to the south. Because the new property is an isolated area—and only recently opened to visitors—most people don’t even know it’s there.

There were no trails, so Gail and I blazed them on our own, even when—later in the summer—the grasses were higher than our heads. Despite the terrain, we showed up week after week with our clipboards and data sheets, counting individuals. We were rewarded with an abundance of Fragile Forktail damselflies and Eastern Forktails (Ischnura verticalis). Although they are both common species in our part of Illinois, their numbers here were noteworthy. We found there are more Fragile Forktails here than at any other location at the Arboretum.

In Illinois, the Fragile Forktail damselflies are designated “S-5,” demonstrably secure in the state. They are ranked “globally secure” by NatureServe. Fragile Forktails are one of five different forktail species found in Illinois and the third most recorded damselfly at The Morton Arboretum. They are one of three forktail species found on the property (Fragile Forktail, Eastern Forktail, and Citrine Forktail (Ischnura hastata)).

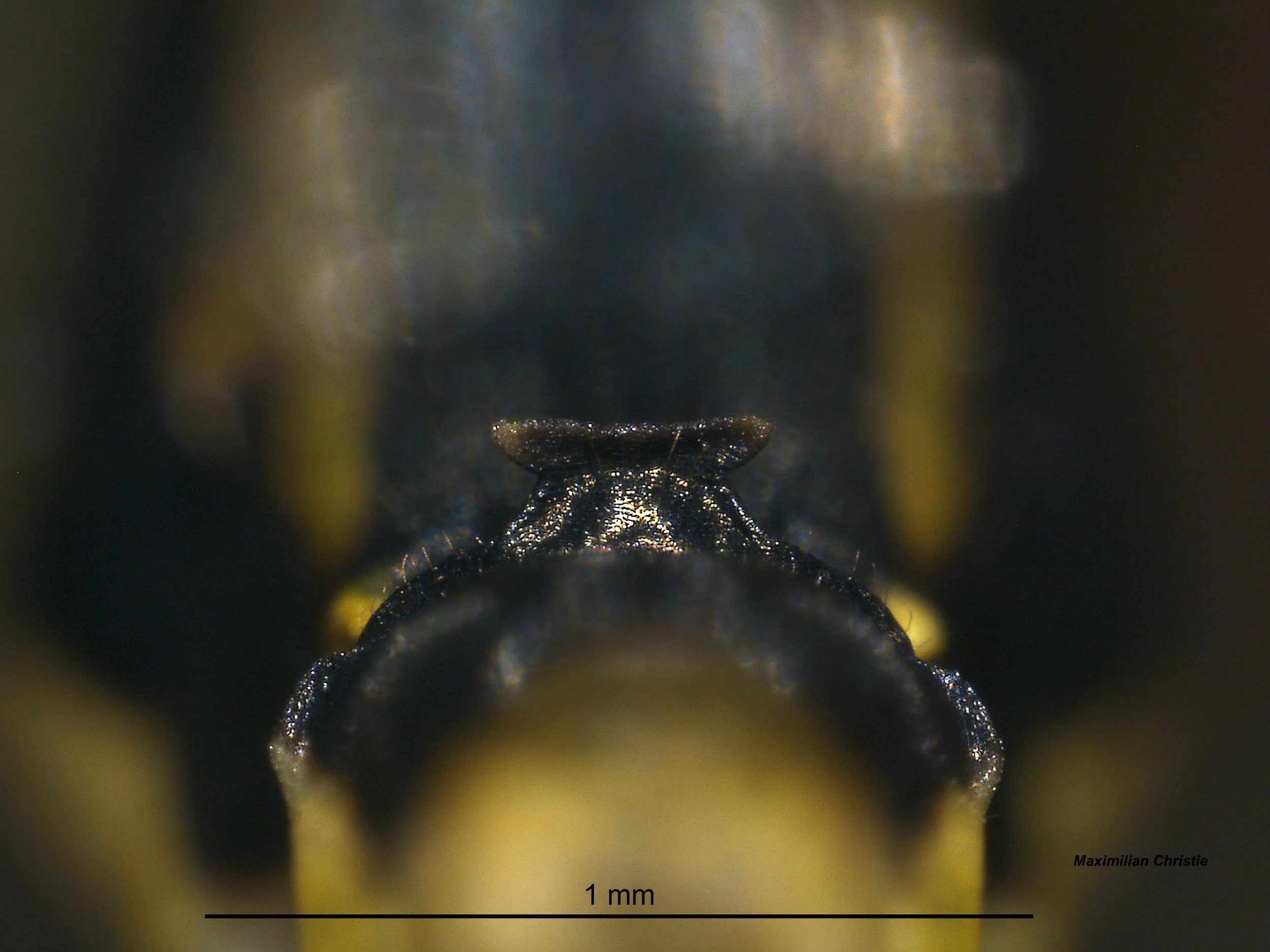

The male Fragile Forktail’s antehumeral (shoulder) stripes on the thorax are yellow-green. The stripe is referred to as “broken,” which can make it look like an exclamation mark (!). This is a key identification feature of the Fragile. They also have dots on the back of their head, so when looking at them from behind, it seems like they are looking at you. The underside of the first and second abdominal segment is black.

The females are similar to males, but the stripes on the thorax and the dots on the back of their heads are blue.

Older Fragile Forktail females, whose blue stripes are obscured with age and pruinosity, can be tough to tell apart from older female Eastern Forktails.

Fragile Forktails typically have a life cycle of one to two years from egg to adult. They prefer quiet waters with lots of aquatic vegetation, into which the females oviposit their eggs. When the eggs hatch, the naiads (nymphs) are said to be pretty feisty, chasing off other naiads.

In addition, Fragile Forktails play a role in the ecosystem as both predators of small insects and prey of birds, frogs, fish, and larger odonates. They contribute to the biodiversity of their habitats. Despite their name, Fragile Forktails are known for their adaptability, including a high tolerance for polluted areas. Fragile Forktails, especially the females, are among the damselflies that eat other damselflies, including those of their own species. Perhaps not so “fragile,” after all!

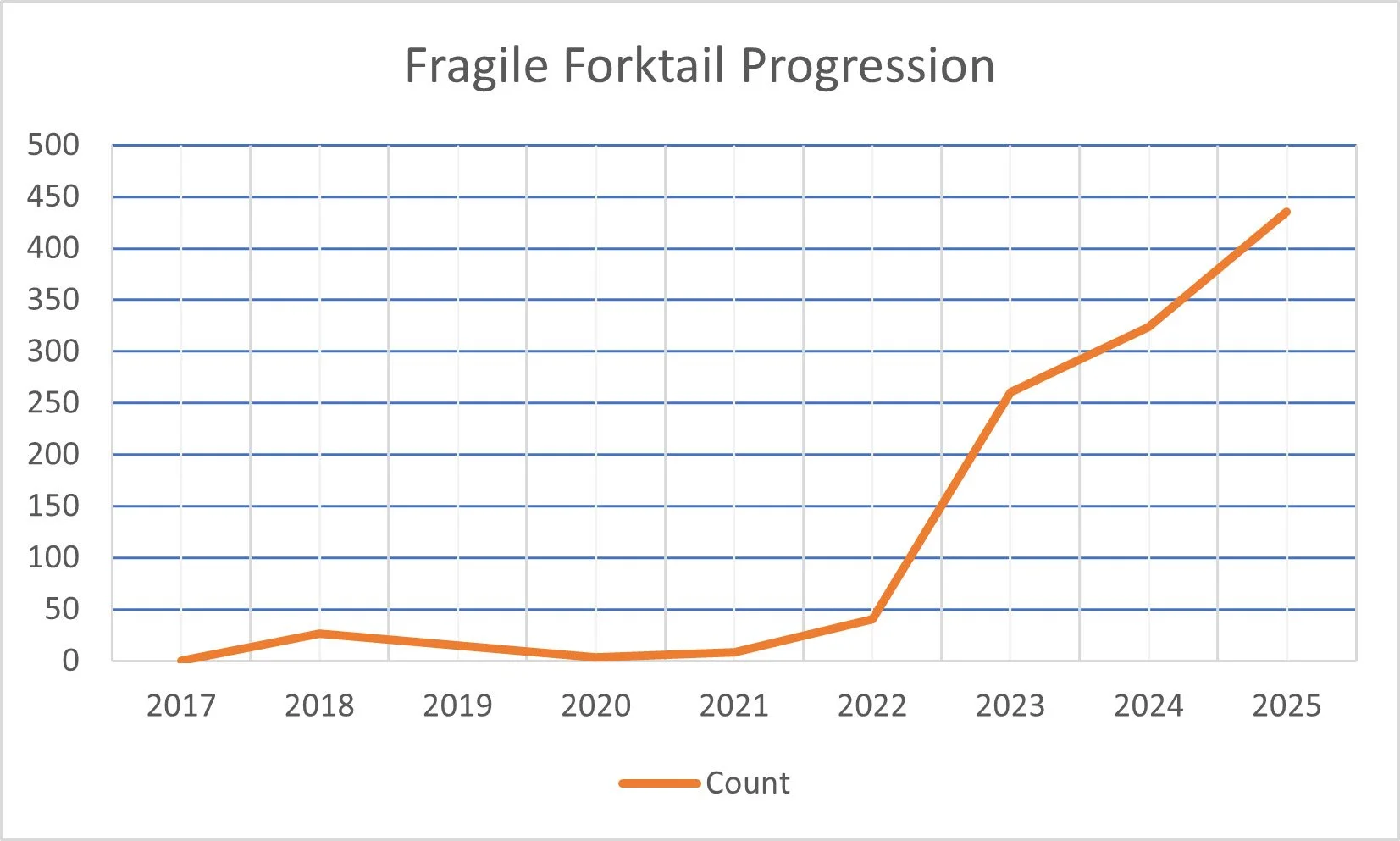

The Fragile Forktail numbers for The Morton Arboretum’s 1,718 acre site as a whole increased by over six times in one year, mostly due to the numbers we found in this new area.

Changes in numbers of recorded Fragile Forktails (Ischnura posita) at The Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Illinois, with the addition of the Fischer Pond site in 2023.

As of 2025, the Fragile Forktails of Fischer Pond are still going strong. We continue to find more each season. Hopefully, 2026 will be another great year for the species at this site.

Steve Baginski took up photography in 1993. As his interest in photography grew, so did his curiosity about the nature he photographed. In 2018, when his wife, Gail Chastain, started volunteering for an Odonata monitoring project at the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Illinois, he began joining her. As his interest in odonates also grew, he officially joined the dragonfly team at The Morton Arboretum in 2020. Steve took special interest in damselflies, as he collected data. Upon retirement, any time he has away from “official” monitoring is now used looking for more dragonflies and damselflies.